The Great AI Decoupling: How Chip Wars and Regulatory Rifts Are Creating Three Separate AI Worlds

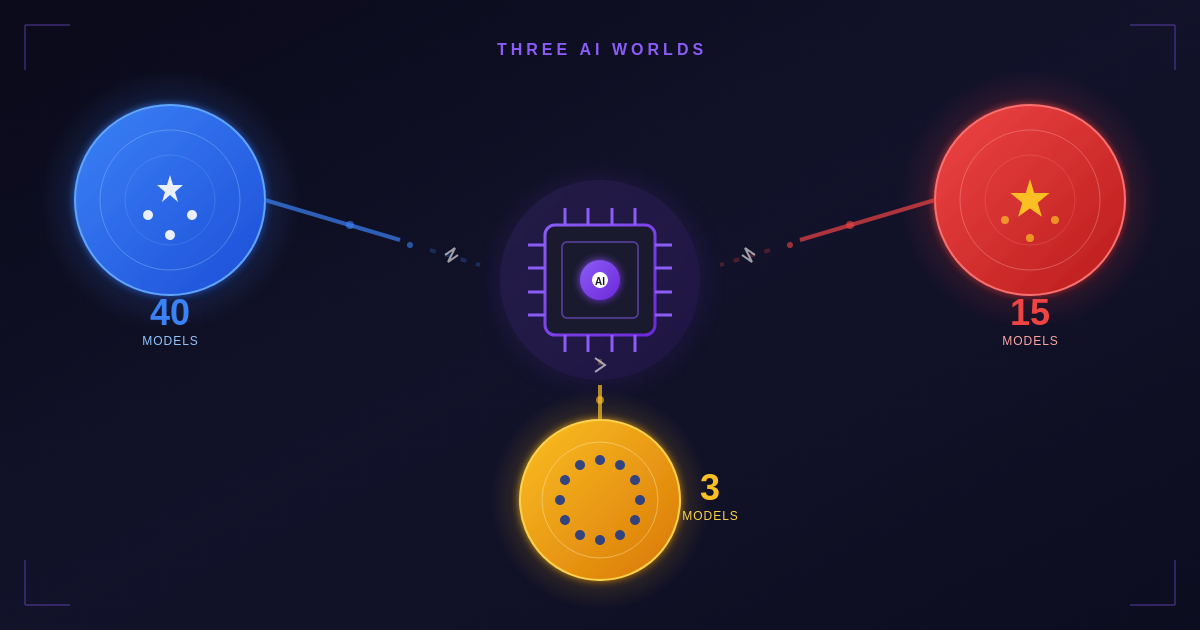

In 2025, global AI fractured into three spheres: US (40 models), China (15), Europe (3). Chip wars and regulations create fragmented ecosystems.

Three AI Superpowers, Three Different Paths

The year 2025 marks a turning point in global AI development. What was once a relatively unified technological frontier has fractured into three distinct spheres, each with its own rules, capabilities, and strategic imperatives. According to Atlantic Council analysis1, the United States produced approximately forty large foundation models in 2025, China around fifteen, and the European Union only about three.

This disparity isn't just about technical capability - it reflects fundamentally different approaches to AI governance, infrastructure investment, and geopolitical strategy. The implications for businesses, particularly those operating across regions, are profound.

Foundation Models by Region (2025)

The Semiconductor Chokepoint

Semiconductors are fundamental to most industrial and national security activities2 and serve as essential building blocks for AI. Policymakers in the United States, China, and elsewhere see semiconductors and AI technologies as critical to future economic competitiveness, national security, and global leadership.

The Biden administration's AI Diffusion Rule, issued in January 2025, represented the most comprehensive attempt to control the flow of advanced AI chips. The Trump administration subsequently rescinded key provisions3, arguing they would stifle American innovation and damage diplomatic relations. But the underlying tension remains.

Export controls have made China a marginal producer of AI chips4. According to congressional testimony, Huawei will produce only 200,000 AI chips in 2025 - a fraction of Nvidia's output. The gap in production capacity represents perhaps the starkest measure of the technological decoupling underway.

AI Chip Production Trajectory (2020-2025)

China's Innovation Paradox

Despite export restrictions, technical benchmarks suggest that China's AI models5 do not have a significant capability gap compared with US-produced models. In some ways, Chinese firms have innovated to work around the limitations of not having high-end chips.

The world was startled in January 2025 when Chinese startup DeepSeek unveiled an open-source research model, R1, which roughly matches the capabilities of advanced models from Google, OpenAI, Meta Platforms, and Anthropic. This achievement demonstrated that computational constraints can drive efficiency innovations.

Chinese firms have responded to chip restrictions by developing more efficient training algorithms, optimizing model architectures for lower-power hardware, and investing heavily in domestic semiconductor development. The result is a parallel AI ecosystem that, while constrained in raw compute, has proven surprisingly capable.

The limits of chip export controls in meeting the China challenge6 are becoming apparent. While they slow China's progress in some areas, they also incentivize innovation and self-reliance. This creates a paradox where restrictions may ultimately strengthen China's long-term AI independence.

Europe's Structural Dependence

Europe's position in the AI decoupling is perhaps the most precarious. The 'big three' US cloud hyperscalers - Amazon, Microsoft, and Google - power about 70% of European digital services1. Europe's domestic semiconductor sector makes up less than 10% of global production.

European AI Infrastructure Dependency

This dependency has profound implications for AI sovereignty. European companies training large models must typically use American cloud infrastructure, subject to US jurisdiction. Data localization requirements create friction but don't fundamentally change the underlying dependency.

The European Commission's AI Continent Action Plan7, unveiled in April 2025, represents the most ambitious attempt to address this gap. The plan includes new AI factories, innovation hubs, pooled resources, improved data access, and accelerated AI application through public services. But implementation remains challenging.

The Biden administration's AI diffusion rule8 had left many European countries facing restrictions on importing advanced chips from the United States. After the Trump administration's rescission, the EU committed to purchasing $40 billion of US-made chips as part of a trade agreement - a decision that some view as deepening rather than reducing dependence.

The Regulatory Divide

Beyond infrastructure, the three AI spheres are diverging on fundamental questions of governance. The United States leans on voluntary risk-management frameworks1 like the NIST AI Risk Management Framework that give firms latitude to innovate. The EU's binding AI Act and sectoral guidance impose high-risk classifications and board-level accountability for AI - raising documentation, testing, and oversight burdens.

AI Regulatory Approach by Region (2025)

The AI Act entered into force on 1 August 20249, with prohibited AI practices and AI literacy obligations applying from February 2025. Governance rules and obligations for general-purpose AI models became applicable in August 2025. The rules for high-risk AI systems embedded in regulated products have an extended transition period until August 2027.

On 19 November 202510, the European Commission proposed targeted amendments to the AI Act as part of the Digital Simplification Package, linking high-risk system rules to the availability of harmonized standards. This flexibility acknowledges the challenges of implementing comprehensive AI regulation.

China's approach differs fundamentally from both. Rather than comprehensive legislation or voluntary frameworks, China relies on sector-specific regulations and direct state guidance. This allows rapid policy adaptation but creates uncertainty for foreign companies operating in the market.

Central and Eastern Europe's Strategic Window

For Central and Eastern Europe, the AI decoupling creates both challenges and opportunities. The region sits at the intersection of EU regulatory requirements and growing interest from both US and Asian technology providers seeking European market access.

CEE Countries AI Readiness Index (2025)

Estonia continues to lead the region in AI readiness, leveraging its digital government infrastructure and startup ecosystem. Poland, despite its larger economy, trails in overall readiness but has significant potential given its strong technical workforce and growing AI investment.

Member States must establish or designate competent authorities11 for AI Act implementation by August 2025. As of late 2025, only three Member States have fully designated both notifying and market surveillance authorities - creating opportunities for countries that move quickly to position themselves as AI regulatory leaders.

The region's relatively lower labor costs and strong STEM education systems make it attractive for AI development centers. Companies seeking to maintain presence in both US and EU AI ecosystems may find CEE an increasingly strategic location.

The Path to AI Sovereignty

The small language model market is projected at USD 0.93 billion in 202512, growing at 28.7% CAGR to reach USD 5.45 billion by 2032. This growth trajectory suggests an alternative path to AI sovereignty - one based on efficient, locally-deployable models rather than massive cloud-based systems.

Small Language Model Market Growth (2025-2032)

The Edge AI market is projected to reach USD 66.47 billion by 203013, growing at 21.7% CAGR. This shift toward on-device processing reduces dependency on foreign cloud infrastructure and may offer Europe and smaller nations a more achievable path to AI independence.

For companies navigating the decoupled AI landscape, small language models offer practical advantages: lower costs, reduced latency, enhanced privacy, and freedom from cross-border data transfer complications. As these models approach the capabilities of their larger counterparts for many applications, they may become the foundation of a more distributed, sovereign AI future.

What Decoupling Means for Business

The fragmentation of the global AI landscape creates significant operational challenges for multinational enterprises. Companies must now consider multiple regulatory frameworks when deploying AI systems across regions.

Understanding US allies' current legal authority14 to implement AI and semiconductor export controls is essential for supply chain planning. Companies may need to maintain separate AI development tracks for different markets, increasing costs and complexity.

US-China chip tensions continue to create uncertainty15 for technology procurement. Companies dependent on advanced AI chips must develop contingency plans for potential supply disruptions while monitoring the evolving export control landscape.

Practical strategies for navigating the decoupled landscape include: building regional AI teams with local regulatory expertise, investing in small language models for applications where they suffice, maintaining flexibility in cloud provider relationships, developing robust data governance frameworks that satisfy multiple jurisdictions, and actively participating in regional standards development.

Living in Three AI Worlds

The great AI decoupling is not a temporary disruption but a structural transformation. The unified global AI landscape that characterized the 2010s has given way to distinct regional ecosystems, each with its own technological trajectory, regulatory philosophy, and strategic priorities.

For businesses, this means abandoning assumptions of a single global AI market. Success will require regional expertise, regulatory agility, and technology strategies that can adapt to divergent requirements. The companies that thrive will be those that treat decoupling not as an obstacle but as a new operating reality.

For policymakers in Central and Eastern Europe, the moment is pivotal. The region has the opportunity to position itself as a bridge between AI ecosystems - a location where companies can maintain compliance with EU regulations while accessing talent and innovation that serves multiple markets.

The three AI worlds are still forming. Their boundaries are not yet fixed, their relationships not yet settled. How nations and companies navigate this transitional period will determine the AI landscape for decades to come.

Sources

- ↑ What drives the divide in transatlantic AI strategy? - Atlantic Council

- ↑ U.S. Export Controls and China: Advanced Semiconductors - Congress.gov

- ↑ Department of Commerce Announces Rescission of Biden-Era AI Diffusion Rule - BIS

- ↑ China's AI Chip Deficit: Why Huawei Can't Catch Nvidia - CFR

- ↑ How US Export Controls Have (and Haven't) Curbed Chinese AI - AI Frontiers

- ↑ The Limits of Chip Export Controls in Meeting the China Challenge - CSIS

- ↑ Making Europe an AI continent - European Parliament

- ↑ The new AI diffusion export control rule will undermine US AI leadership - Brookings

- ↑ AI Act - Shaping Europe's digital future - European Commission

- ↑ EU AI Act Implementation Timeline

- ↑ Overview of all AI Act National Implementation Plans

- ↑ Small Language Model Market 2025: AI Goes Light, Fast, And Local - MarketsandMarkets

- ↑ Edge AI Market Size, Share & Growth | Industry Report, 2030

- ↑ Understanding U.S. Allies' Current Legal Authority to Implement AI and Semiconductor Export Controls - CSIS

- ↑ U.S.-China Chip Tensions Renew Focus on AI Controls - FinTech Weekly