Artificial Intelligence and Big Politics: Under the Shadow of Threats - Are Regulations Necessary?

An analysis of AI regulations in the context of global politics, examining the balance between innovation and security concerns.

Artificial Intelligence and Big Politics — Under the Shadow of Threats. Are Regulations Necessary?

We live in a time where technology, media, and politics intertwine like never before. Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram have become essential tools for political communication. Politicians can communicate directly with voters, mobilize support, and organize campaigns through them. A chart from Statista shows the vast percentage of each country's population using social media worldwide1. In 2023, China had over a billion social media users, making it the country with the highest number of users. It is expected that by 2029, this number will exceed 1.2 billion. However, India is set to take the lead, reaching 1.3 billion users by 2029. Meanwhile, the number of social media users in Nigeria is expected to rise from 47 million in 2023 to 114 million in 2029, indicating a 142% increase. The "digital electorate" is, therefore, the future for politicians.

Social Media Users by Country (2023-2029)

Brexit: Social Media's Political Power

However, social media can also be a source of disinformation and fake news, posing a serious challenge to modern democracy. This issue becomes evident, for example, during the upcoming presidential elections in the United States, where the Republican candidate Donald Trump recently falsely accused his main rival, Kamala Harris, of using AI-generated images2 to inflate crowd sizes at her events.

Discussing the influence of social media on contemporary politics is incomplete without mentioning an intriguing case study analysis from the European Parliamentary Research Service published in 20193. The authors examined how emotions and social media can influence public opinion and election results, particularly during Brexit. The 2016 UK European Union membership referendum was the first "digital referendum." Both campaigns—Leave and Remain—focused on online strategies, and social media played a crucial role in the dissemination of information. At that time, 41% of British internet users received news via social media, mainly from Facebook (29%) and Twitter (12%). During the campaign, nearly 15,000 articles related to the referendum were published. The media focused on various issues such as the economy, immigration, and health, but the tone of coverage was often biased and emotional. The Leave campaign was more effective on social media due to its more emotional messaging. Topics like immigration were frequently discussed in a negative light, with the number of reports tripling during the 10-week campaign. Posts by Leave supporters on Instagram received 26% more likes and 20% more comments than those by Remain, and the most active users campaigned for Leave. On Facebook, nearly half of the most engaging pages were openly pro-Brexit, generating over 11 million interactions—three times more than pro-Remain pages. Thus, the mechanisms by which social media platforms amplify certain messages can have real and sometimes irreversible consequences.

Brexit Campaign Social Media Engagement

Deep Fakes and Disinformation

Returning to dishonest practices in the virtual space, fake news involves false or partially false information posted online to mislead audiences. This manipulation method is often used for financial or political gains. Unfortunately, this practice is toxic to public debate and significantly deepens social polarization. Another "invention" for falsifying the infosphere is so-called deep fake. This synthetic media involves AI-manipulated or generated images, videos, or audio to create a highly realistic but fundamentally false effect. Deep fakes use machine learning techniques like Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN)4 to map and replicate a person's facial expressions, voice, and movements.

Like fake news, this technology can be used to spread disinformation. In the third week of August, a video by @thedorbrothers appeared on platform X5 (formerly Twitter), showing well-known influential figures such as Joe Biden, Donald Trump, Kamala Harris, Mark Zuckerberg, and even Pope Francis, allegedly robbing stores with weapons in hand. The realism level of this production is impressive, demonstrating current technological capabilities in this field. Considering that tools for creating such materials are continually being developed and improved, it could be said that in the perhaps not-so-distant future, false content will be so difficult to identify, leading to an information chaos overload and waves of lawsuits or other forms of social resonance, since accusations based on false evidence could involve any of us. How, without a legal basis, can one prove they didn't commit a crime or violation?

Fighting Deepfakes with AI

Ironically, AI is also used in the fight against fake content. Deepfake materials, thanks to mass access to images and videos, are increasingly common on social media, necessitating effective detection. In response, organizations like DARPA6, Facebook7, and Google are conducting extensive research into deepfake detection methods8 using various deep learning approaches, such as LSTM or RNN.

A specific example of an innovative detection tool is McAfee's Deepfake Detector, released in August 20249. This groundbreaking tool detects audio deepfakes by analyzing sound in videos and streams on platforms like YouTube and X (formerly Twitter), warning users about potential deepfakes. It operates directly on users' devices, ensuring privacy but does not support DRM-protected content.

AI Developers Acknowledge the Risks – Recent Reports

In August 2024, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology published an AI Risk Repository, a database containing over 700 AI-related threats10. This repository, developed from 43 existing risk frameworks and classifications, is divided into three main parts: the AI Risk Database, detailing risks, quotes, and page numbers from original sources; the Causal Taxonomy of AI Risks, classifying risks by cause, timing, and occurrence; and the Domain Taxonomy of AI Risks, dividing risks into seven main domains and 23 sub-domains, such as disinformation and privacy. This compilation aims to provide an overview of the AI threat landscape, with regularly updated information sources and a common reference framework for researchers, developers, companies, auditors, policymakers, and regulators.

In this context, it's worth mentioning that OpenAI recently expressed concerns about users developing emotional attachments to the new ChatGPT-4o model11. Thanks to its advanced capabilities, the model generates more realistic responses, leading to situations where users might attribute human-like characteristics and form emotional bonds with it. The company noted that some users used language suggesting bond formation with the model, which could cause problems for both individuals and society.

"During early testing, including red teaming and internal user testing, we observed that users used language that might indicate forming connections with the model. [...] Human-like socialization with an AI model could cause spillover effects on interpersonal interactions. For example, users might form social relationships with AI, reducing their need for human interaction—potentially beneficial for lonely individuals but potentially impacting healthy relationships. Extended interaction with the model could impact social norms."

OpenAI warns that such behavior could diminish the need for human interaction and affect healthy relationships. Thus, the company plans further research on the potential effects of emotional attachment to AI and ways to limit it.

Interestingly, the company report on GPT-4o also assessed how articles and chatbots generated by the new flagship model influenced participants' opinions on political topics11. It turned out that AI wasn't more persuasive than humans, but in three out of twelve cases, AI was more persuasive. The study examined how audio clips and interactive conversations generated by GPT-4o influence participants' political preferences. AI wasn't more convincing than humans. AI audio clips had 78% of the effectiveness of human audio clips, and AI conversations had 65% of the effectiveness of human conversations. A week after the study, the durability of opinion changes was checked. The AI conversation effect was 0.8%, and audio clips -0.72%.

GPT-4o vs Human Persuasiveness in Political Topics

The Regulatory Environment for AI — Necessary or Not?

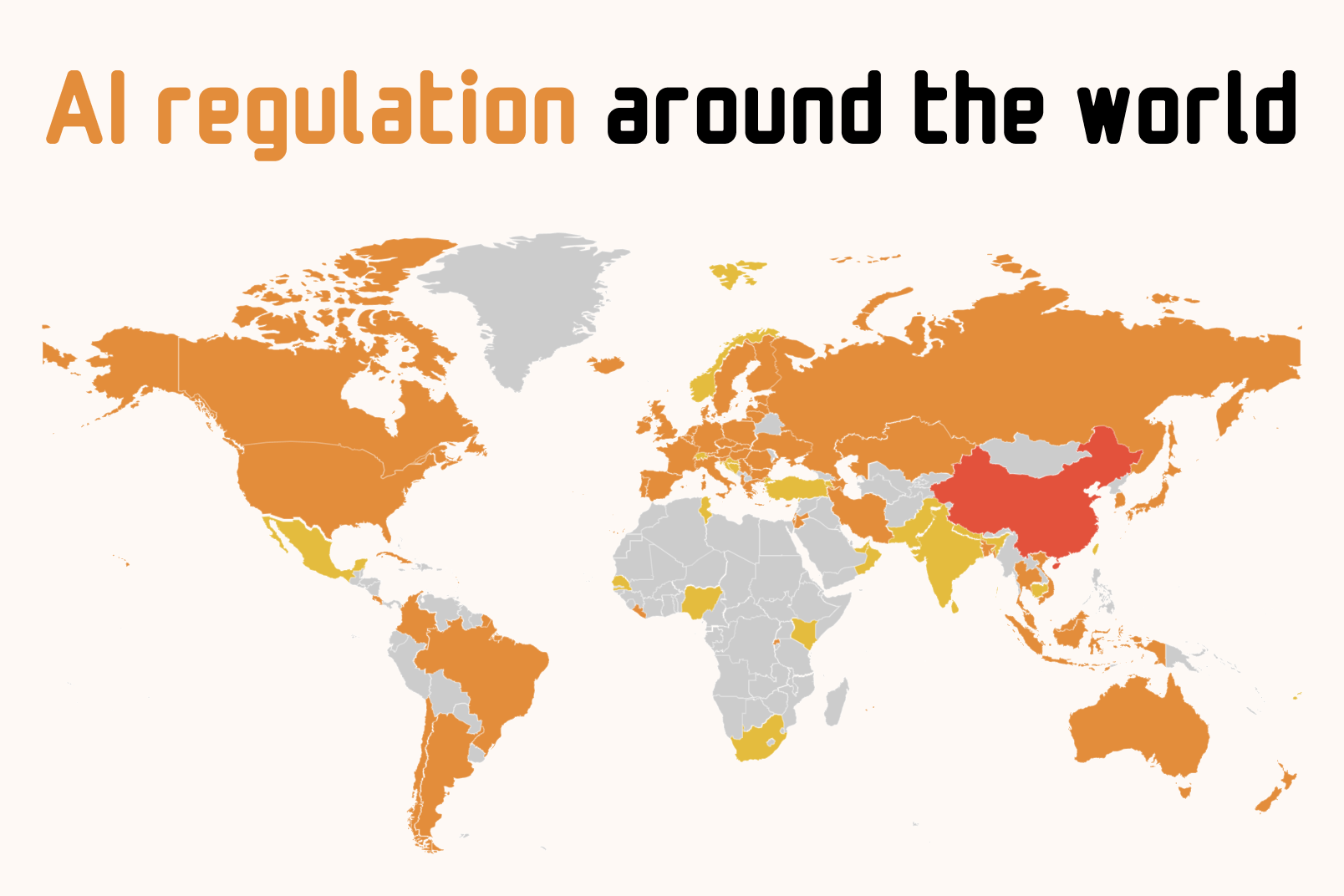

Laws clearly lag behind technology. In cyberspace, offenders involved in various abuses often remain elusive, making them feel "immune" to consequences. In criminal activities, modern technologies, including artificial intelligence, are increasingly effectively used, for example, to steal individuals' savings or acquire sensitive personal data. Thus, the critical question arises about the need for legal regulations in this area. The map below shows the stance of European countries regarding the introduction of AI regulations12 at the national level.

Considering that AI developers themselves research and indicate the risks associated with its use, the need for legal regulations seems apparent. The essential question remains the scope of these regulations.

Global AI Regulations Comparison

| Region/Country | Regulation | Year | Key Features | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Union | AI Act | 2024 | Risk-based framework, transparency requirements, labeling AI content | Active |

| Brazil | AI Law (Bill 2338/2023) | 2021 | Data protection focus, ANPD enforcement, restrictions on training data | Active |

| USA (California) | SB-1047 | 2024 | Safety requirements for large models ($100M+ compute), critical harm prevention | Proposed |

The European Union was the first major entity to introduce legislation concerning artificial intelligence. The so-called AI Act, published on July 12, 202413, is a document aimed at establishing a unified legal framework for the development, implementation, and use of AI systems within the EU. The directive includes several assumptions to protect European community citizens. It ensures developing safe and ethical AI systems respecting citizens' rights and mandates algorithm transparency and labeling AI-generated content. Moreover, it sets rules for managing the entire AI system lifecycle, from design to use, and outlines AI utilization guidelines for the public sector, including by law enforcement and in electoral processes or courts. Notably, the comprehensive EU regulation also includes the AI Act Compliance Checker, a tool helpful for small and medium enterprises, as well as startups, to check if their AI systems comply with the EU act. Currently, this tool is in preparation.

On the downside, the document adopted by the European Parliament significantly limits Europe's technological advancement and deprives it of the opportunity to develop modern technologies on an equal or similar level to other key players on the international stage, like China or the USA. Evidence can be found in the recent announcement that Meta does not plan to introduce its multimodal AI model Llama 3.1 405B in the European Union due to regulatory concerns14. Previously, Apple made a similar decision, excluding the EU market from the launch of Apple Intelligence15.

Another example of an AI regulatory body is Brazil, which already in 2021 approved an AI law16. Although initially, it didn't ensure sufficient transparency, among other things, Brazilian legislators are working on improvements. In July 2024, Brazil's National Data Protection Agency (ANPD) ordered Meta to stop using Facebook and Instagram data for training its AI models17. This decision followed a Human Rights Watch report showing that a popular dataset used for AI model training contained photos of Brazilian children18, posing a risk of their use in deepfakes or other forms of exploitation. Commenting on the issue, Meta firmly stated that their policy "complies with Brazilian privacy laws and regulations," and the ANPD decision is "a step back for innovation, competition in the AI development, and further delays in delivering AI benefits to people in Brazil."

In late August 2024, California also published a bill draft aimed at regulating the most powerful AI models19. The bill requires creators of AI models using computing resources worth over $100 million to adhere to and disclose a Safety Plan to prevent their models from causing "critical harm." If adopted, it could bolster the EU's position in regulating AI and inspire other states to create their regulations. Some companies, like Anthropic, support the bill after amendments20, and Elon Musk suggests its enactment. However, the bill also faces a broad opposition from both the industry and Democrats in the US Congress. Meta, OpenAI, Google, and other companies oppose this regulation's introduction21, arguing it would harm open-source software development and AI innovation. The bill needs approval from the General Assembly by August 31, then endorsement by the Senate and a signature from California's governor. Democrats in Congress and the US Chamber of Commerce urge Newsom to veto the bill.

These are just a few examples of how global entities try to "frame" artificial intelligence in regulatory contexts. Although we are in the early phase of this process, it can be assumed that shaping the legal environment for AI will be complex since it must consider this technology's development pace, which is indeed impressive.

Regulations – What's Next?

Every new technology comes with both opportunities and threats. Artificial intelligence serves as a valuable assistant in many industries, but the benefits of its development must align with safety. Risk identification and a legal environment are equally important in this case. The mentioned AI Act provides users—the individuals whom artificial intelligence affects—with the defense of their rights, safety guarantees, and a regulatory framework for its use. However, slowing or natural development of AI technology due to market regulations is a fact. Europe deprives itself of technological sovereignty and widens the gap compared to global players. The directive poses constraints for both local producers and consumers and serves as a significant challenge for non-EU companies that won't be able to offer their products and services in one of the world's largest economic markets.

In conclusion, while establishing regulatory frameworks is essential for the proper functioning of businesses and societies as new technologies evolve, it requires a nuanced approach that ensures user comfort while not hindering societal and economic progress. But is it possible to balance these? Crafting an optimal solution will be a considerable challenge, particularly considering AI's development dynamics. There is indeed a risk that entities, which, in principle, do not prioritize data protection, for example, could gain such an edge in the technological race that it may become unattainable.

Sources

- ↑ Number of social media users in selected countries in 2023 and 2029

- ↑ Trump falsely claims Harris crowd photos were AI-generated

- ↑ The impact of disinformation on democratic processes and human rights: Brexit case study

- ↑ Generative Adversarial Networks: A Survey and Taxonomy

- ↑ Deepfake video showing world leaders robbing stores

- ↑ DARPA Media Forensics (MediFor) Program

- ↑ Facebook Deepfake Detection Challenge

- ↑ Google's Deepfake Detection Research

- ↑ McAfee launches Deepfake Audio Detector

- ↑ MIT AI Risk Repository: A Comprehensive Database of AI Risks

- ↑ GPT-4o System Card

- ↑ AI regulation around the world

- ↑ Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 on Artificial Intelligence

- ↑ Meta delays EU release of Llama AI model over regulatory concerns

- ↑ Apple to delay AI features in EU over regulatory concerns

- ↑ Brazil's Artificial Intelligence Bill

- ↑ Brazil halts Meta's plans to use social media posts for AI training

- ↑ How AI Can Harm Children's Privacy and Safety

- ↑ California Senate Bill 1047: Safe and Secure Innovation for Frontier Artificial Intelligence Models Act

- ↑ Anthropic's letter supporting California SB 1047 with amendments

- ↑ Tech giants oppose California AI safety bill